The beauty in the harmonic and organic actions of actors and drummers in Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ

Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ is a ritual and theatrical art evolved to its contemporary form over several centuries. Rooted in the ancient Indian theatrical tradition, it was nurtured for centuries by the Brahmanical temple culture and performed for the exclusive audience of the temple elites. It survived the collapse of temple society resulting from the land reform of the post India independence and reached the 21st century thanks to a tiny group of performers who still maintain it either as traditionally inherited family right of specific communities, namely Cākyārs (actors) and Nambyārs (drummers), or having learnt it at the Kalamandalam or other institutions such as Margi in Trivandrum, Ammannur Gurukulam and Natanakairali at Irinjalakuda. While Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ is at present performed in theatres, auditoriums and a number of other venues by actors and drummers belonging to any community, the exclusive right to perform inside temples still retained by Cākyārs and Nambyārs.

Notwithstanding the fact that, over the last few decades, some aspects have been adapted in order to make it more suitable to the needs of the new audiences attending performances in auditoriums and no more in temple theaters (kūttambalams), this art form is still filled with a medieval flavor. Intricate face painting, rich costumes, big headgears, codified hand gestures (mudrās), minute facial expressions characterize its acting technique and its sonic ambience is dominated by the sound of drums, the pot drum miḻāvu and the tension hourglass drum idakkya, and punctuated by the voice of the actors chanting Sanskrit texts in a way peculiar to this art form. Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ is a multifaceted theatrical form which asks to the performers, both actors and musicians, to control a number of aspects at the same time. But it also asks to its public specific qualities and abilities to fully appreciate it in its complexity. Furthermore, although contemporary staging usually lasts a couple of hours, some performances may last up to six hours. All these features explain why the audiences are not numerous.

From left to right: Kalamandalam Ashwathy, Sangeet Cākyār, Kalamandalam Rahul, Kalamandalam Sajith Vijayan and Kalanilayam Rajan

For the last few years, I have been conducting fieldwork on ritual drumming in Kerala focusing on the relationship of drumming and images – intended as sculptured, painted, verbal as well as performed representations – and Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ was one of the ritual performances which I studied. I have been attending a number of dramas in order to study the language and repertoire of the miḻāvu and the way its sound leads, enlivens and interacts with the movements of the actors on the scene and gives expression to the emotions of the characters. According to my findings, the voice of the miḻāvu does not only accompany the actions of the actors, as generally believed, but generates and completes them. As I have argued in a recent article, by playing the miḻāvoccappeṭuttal, the composition which gives the start to every Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ performance, the drummer creates an entire universe which is later displayed by the actors on the stage. Indeed, through this composition, the sound of the drum enlivens the stage by summoning the deities into it and then gives birth to the characters and their stories. The voice of the miḻāvu is the source of the performance, it is the breath of the actors and gives sonic shape to their thoughts and emotions. It is for these reasons that actors salute it as soon as they enter the stage.

In other words, in my view, contrasting with the contemporary approach which tends to consider actors as the leaders of the performance and drummers as their accompanists, drummers and actors should be conceived as equally important and they should actually interact as two elements of a single body. In fact, the body of drama may really take life when they deeply join their minds, hearts and techniques. While Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ performers, both actors and drummers, are generally good and the quality of their interaction on the stage is high, rarely such kind of organic unity is created.

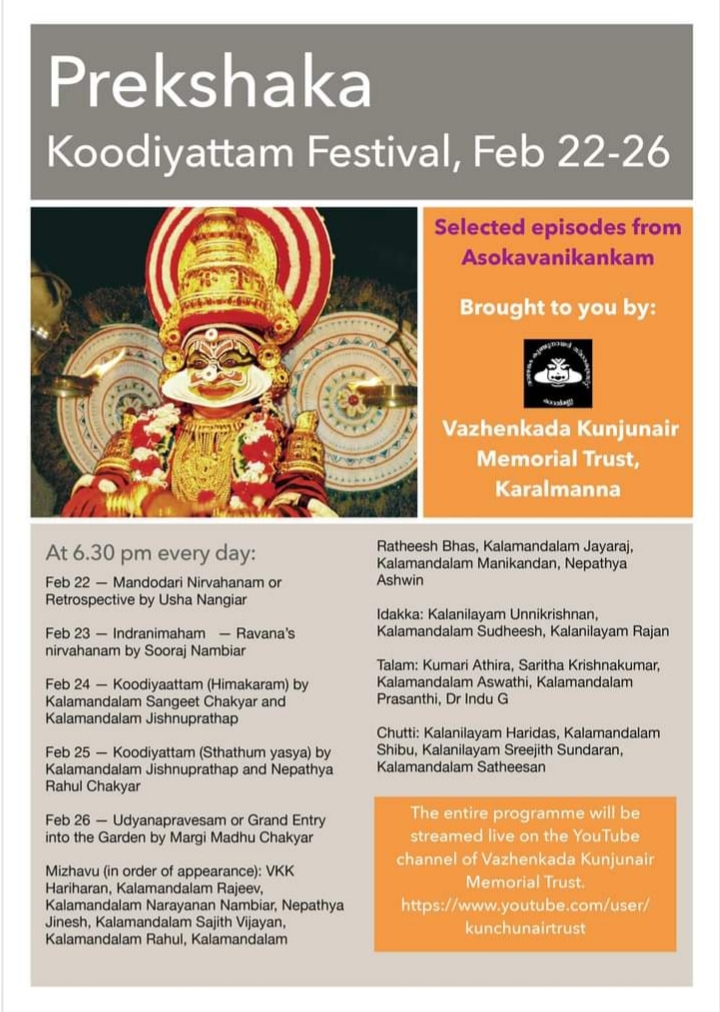

I recently had the chance to attend one of such performances. It was staged by leading artists such as Sangeet Chakyar, Kalamandalam Jeshnuprathap (acting), Kalamandalam Sajith Vijayan and Kalamandalam Rahul (miḻāvu), Kalanilayam Rajan (idakkya), Kalamandalam Ashwathy (tālam), and Kalamandalam Shibu (chutty/face painting). The performance was part of the ‘Prekshaka’ Kūtiyāṭṭaṃ festival – held at the Vazhenkada Kunjunair Memorial Trust, Karalmanna (Feb 22-26/2022) – whose program included some of the most renowned performers.

The deep quality of the interaction between the drummers and the two characters, interpreted by two different actors, was very high and sensitive during the entire performance. Indeed, the gorgeous palette of face expressions and the powerful dynamism of the body of the actors was enlivened by the equally wide range of sounds and energy produced by the careful musicians and the result was that they all were moving as a single body.

While battles scenes, where actors may display their energy and act with their full body and drummers have to energetically strike the skin of the miḻāvu to produce its fierce voice, are particularly strong, theatrically efficacious and hence relatively simple, romantic and introverted scenes are delicate and risky. Indeed, in such scenes the actor, standing or sat on a stool, has to narrate his/her own feelings in a detailed and intimate manner by means of minute eye expressions and codified hand gestures and the drummers have to play slow or middle speed tālas with dynamics ranging between piano and mezzo forte. This kind of delicate and detailed scenes are particularly demanding for the audience’s attention and participation, in particular when they last more than twenty minutes.

The performers displayed their abilities in both the contexts. The rendition of the slow tālas was never obvious and always matching the fine nuances of the emotions of Ravana lost in his desire for Sita and Sangeet Chakyar, enacting Ravana, was in turn, keen to set all his face and bodily actions – even the minutest – on the strokes of the miḻāvus. Both acting and drumming where always balanced and finely presented. In a similar way, Jeshnupratap enacted Ravana’s minister Chitrayodhi in synchronic harmony with the drummers.

Overall, the performance progressed in a crescendo of intensity of sounds and actions which reached its peak in the last section and when all the actors were on the stage performing controlled energetic movements generated and supported by the fierce voice of the miḻāvus forcefully struck by the drummers.

This elegant performance, from my point of view, showed the beauty which may result from the well-balanced interaction of music and action, musicians and actors, as it is implied in the concept itself of this unique art form.

Photo by Paolo Pacciolla